In this paper I analyse the first

chapter of Meister Eckharts ›Auslegung des Buches Genesis‹. I show how the

systematic thinking of Meister Eckhart, which is introduced in the first part

of his latin work, is fundamental for the understanding of his entire work. The

dynamic relation is more important than the any absolute principal. And only

through the consideration of the relation can love and deficiency be

understood. The focus in this paper is the first chapter of the ›Auslegung des

Buches Genesis‹. Eckhart explains the structure of thinking parallel to the

formation of the universe.

Showing posts with label Meister Eckhart. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Meister Eckhart. Show all posts

Friday, 4 January 2019

Wednesday, 14 November 2018

Dietamr Mieth presents a working paper on 'The "heart" as a metaphorical-real speech within Meister Eckharts work'

Meister Eckhart is known as an author who enriches mysticism but is at

the same time very intellectual/rational. Philosophers seem to present another

Eckhart than those who read him spiritually. The connection between both

approaches is given by Eckhart himself: the “heart” is the real embodiment of rational thinking and it is the center of his

metaphorical language concerning the presence of God in the soul. Eckhart’s preaching

in High-Middle German integrates real and metaporical considerations, but

for him the metaphors represent the reality insofar as God’s reality is the

true agent. In the colloquium the rich and different aspects of Eckhart’s preaching

from ‘heart to heart’ will be investigated

Wednesday, 23 May 2018

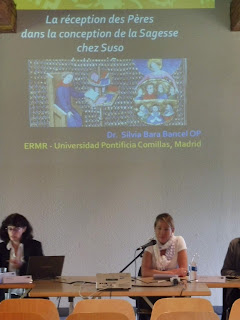

Meister Eckhart and the Church Fathers - First workshop of the joint French-German Project at Metz

On 16./17. May 2018, the two groups of French and German researchers met for their first workshop as part of the joint project, financed by the French ANR and the German DFG to explore the sources and traditions on which Meister Eckhart based his works.

The workshop questioned the anachronistic concepts of 'quotation' or 'citation', of 'reception' and 'transmission', as Eckhart shows an enormous variety of dealing with older traditions and authorities that can hardly been captured by the existing nomenclature. The project is run under the leadership of Marie-Ann Vannier (University of Lorraine, Metz) and Markus Vinzent (King's College London and Max-Weber-Kolleg, Erfurt).

The project that is running for three years will develop conceptual tools in understanding the different ways Eckhart appropriates and makes his own Patristic authorities, publish the papers of conferences, monographs on specific authors who have a particular importance in Eckhart (Origen, Augustine, Pseudo-Chrysostom, Jerome, Maximus Confessor, John of Damascus, Albertus Magnus) or for Eckhart (Nicolaus Cusanus and Henry Suso). Unfortunately, we do not have pictures of all speakers - so here the few snapshots:

The project will also create the Patristic Index for the critical edition of Eckhart's works in the Kohlhammer edition (to follow the first volume of the Bibleindex, published by Loris Sturlese and Markus Vinzent in 2015).

And, of course, we celebrated being together with typical French conviviality (for which we thank the French team and the University of Lorraine for all their hard work, preparation, organisation and finance):

The project that is running for three years will develop conceptual tools in understanding the different ways Eckhart appropriates and makes his own Patristic authorities, publish the papers of conferences, monographs on specific authors who have a particular importance in Eckhart (Origen, Augustine, Pseudo-Chrysostom, Jerome, Maximus Confessor, John of Damascus, Albertus Magnus) or for Eckhart (Nicolaus Cusanus and Henry Suso). Unfortunately, we do not have pictures of all speakers - so here the few snapshots:

Silvia Bara Bancel (Université de Madrid) and Elisabeth Boncour (Université catholique de Lyon)

Jacques Elfassi (Université de Lorraine) on Eckhart and Isidore of Seville

Jana Ilnicka (mid) on Eckhart and Boethius

Dietmar Mieth on Eckhart and the tradition of action and contemplation

Jean-Claude Lagarrigue (ERMR Strasbourg) and Julie Casteigt (Université de Toulouse II)

The project will also create the Patristic Index for the critical edition of Eckhart's works in the Kohlhammer edition (to follow the first volume of the Bibleindex, published by Loris Sturlese and Markus Vinzent in 2015).

And, of course, we celebrated being together with typical French conviviality (for which we thank the French team and the University of Lorraine for all their hard work, preparation, organisation and finance):

Tuesday, 8 May 2018

Sarah Al-Taher presents a working paper on 'Prologi in Opus tripartitum – the systematic thinking of Meister eckhart'

In this paper I approach the systematic thinking of Meister Eckhart in his latin work, especially in his general introduction to the three parts of his latin work ( ›Prologi in Opus tripartitum‹.). I concentrate mostly on the first part which deals with 14 theses. These 14 theses are divided into opposite terms. The most important one being “being” and “nothing”. I try to analyse Eckhart’s dualistic thinking by maintaining a unified prin-ciple. The Question of the understanding of “being”, “nothing” and “not-being” stand in the centre of this paper, as they can give an under-standing to Eckhart’s systematic thinking. Thus, allowing to analyse the concept of deficiency and love within Eckhart’s work in a next step.

Wednesday, 2 May 2018

Jana Ilnicka presents a working paper on 'Meister Eckhart and Boethius De Trinitate: searching for the sources of Meister Eckhart

In this brief paper, I try to examine how Meister Eckhart works with his sources. Using the example of a difficult text by Eckhart, which I examined in my recently completed phd thesis, I show that not only explicit citations in the works of Meister Eckhart, but also his implicit work with the texts of the auctoritates an importance for the source research of Meister Eckhart.

Thursday, 11 January 2018

Sarah Al-Taher is going to present a working paper on 'An approach to the concept of lack/deficiency and its meaning in Meister Eckhart's work'

In this paper I try to develop a concept of “deficiency” (Mangel) in the German Work of Meister Eckhart. Looking into the Concept of deficiency in all its variations, leads to the necessity of also considering Eckhart’s use of the Terms „Nothing“ and „Being“.

I divided the relevant texts of Eckhart into two categories: (1)Metaphysical, ontological questions and (2) texts about virtue. This allows a wide Concept of deficiency which will be discussed it the paper.

I divided the relevant texts of Eckhart into two categories: (1)Metaphysical, ontological questions and (2) texts about virtue. This allows a wide Concept of deficiency which will be discussed it the paper.

Saturday, 16 December 2017

Jana Ilnicka gives a working paper on 'Responsiones Prosperi'

In this paper, I consider two short texts by Prosper de Regio Emilia, who compiled the manuscript Vat. Lat. 1086. These texts are unusual and difficult to fully understand unless considered alongside those from university disputations of the 13th and 14th centuries, because the style and structure of the various types of questions, and their background, along with the nature of the disputation, can all supply information that will enrich and indeed clarify the texts. The texts show how strongly Prosper was influenced by Meister Eckhart, especially on the subject of ‘relationship’.

Thursday, 23 November 2017

Julie Casteigt is going to present a working paper on 'Thinking in images and through images: Eckharts one-being in the other'

In this workshop, I would like to examine the problem and the method of my next book Mutuality and pocessual Thinking: Meister Eckhart and focus on the concept of reciprocal inbeing. The reason for choosing this topic is to develop the broader problem of dynamic unity in the context of a processual thinking. Here I concentrate on the commentary of a single verse (Jn 10:38) and the network of verses to which this commentary refers. In doing so, I would like to show how the metaphysical unfolding of the concept of “Being-‐one in the other” is inseparable from the exegetical

method of Eckhart. The reciprocal inbeing of the Father and the Son in the biblical verse is not only to be metaphysically understood in the framework of the theory of participation, but as the mutually constituting being of two correlative terms. In order to think processually of the mfutual being, Eckhart uses an exegetical method that links one biblical image with another. At the same time, he develops his doctrine of image as an image, or as an example, of the Being-‐one and of the inbeing of

the Father and of the Son.

method of Eckhart. The reciprocal inbeing of the Father and the Son in the biblical verse is not only to be metaphysically understood in the framework of the theory of participation, but as the mutually constituting being of two correlative terms. In order to think processually of the mfutual being, Eckhart uses an exegetical method that links one biblical image with another. At the same time, he develops his doctrine of image as an image, or as an example, of the Being-‐one and of the inbeing of

the Father and of the Son.

Thursday, 20 April 2017

Jana Ilnicka is going to present a working paper on 'Die Göttliche Selbstbestimmung und Personkonstituierung nach Meister Eckhart' (Divine Self-constitution and constitution of personhood in Meister Eckhart)

In this paper I am dealing with the question of relation, from the newly re-discovered manuscript of Wartburg, in comparison with certain German sermons of Meister Eckhart. The question on the Wartburg manuscript shows many parallels with other texts of Eckhart and offers a more explicit representation of his ideas.

Tuesday, 24 January 2017

Andrés Quero-Sánchez presents a paper on 'Meister Eckhart’s Rede von der armuot in the Netherlands: Ruusbroec’s Critique and Geert Grote’s Sermon on Poverty'

At the very beginning of his well-known interpretation of Meister Eckhart’s Sermon on Poverty

in the first volume of Lectura Eckhardi, that is to say: of his interpretation of Eckhart’s German

Sermon 52 according to the numeration by JOSEF QUINT, KURT FLASCH states: ‘This sermon is

a beautiful one’.

Although I myself do think that this text by Eckhart – which not only Valentin

Weigel (d. 1588), Pelgrim Pullen (d. 1608), Jacob Boehme (d. 1624) and Angelus Silesius (d.

1677) but also Schelling (d. 1854) and even Nietzsche (d. 1900) knew and highly valued

– is

to be seen as one of the most important works in the history of German philosophy – or, maybe,

Theology –, I do not think that FLASCH‘s assertion is a true one. Why not? I will answer this

question in a moment, but let me first raise another question – the following one: Being, as it is,

a particularly radical text, including some theses which are – or, at least, seem to be – especially

unorthodox, how could it be that no sentence of this sermon was discussed in the context of

Eckhart’s inquisition trial? For, as KURT RUH expressed , the inquisitors ‘could not have found a better text’ for their purposes.

That is surely particularly right of the sentence that – to give

you a well-known example – Nietzsche quotes in The Gay Science: ‘I pray God to liberate me

from God’ (sô bite ich got, daz er mich quît mache gotes).

For, as Eckhart in the continuation

of the passage says, if God is rightly conceived, ‘I am then the cause of myself’ (sô bin ich mîn

selbes sache).

Some scholars, with EDMUND COLLEDGE and JACK C. MARLER leading the way,

tried to find an explanation for this problem by stating that Eckhart had given that Sermon on

Poverty in the last years of his life, as his inquisition trial was already ongoing: ‘The Sermon

[on Poverty] was too late for it to be used against him’.

However, I think that there is another, more natural explanation for that apparently

incomprehensible fact. At the beginning of the text, Eckhart actually speaks not of a ‘Sermon’

but of a ‘rede’, that is, a ‘Speech’ or ‘Lecture’, by saying: ‘Now, I beg you to be so that you

can understand dise rede [i.e. this Speech or Lecture]’ (Nû bite ich iuch, daz ir alsô sît, daz ir

verstât dise rede).

And at the end of the text, he says in a similar manner: ‘For as long as man

has not become identical with truth, he will not understand dise rede [here again, this Speech

or Lecture]’ (Wan alsô lange der mensche niht glîch enist dirre wârheit, sô lange ensol er dise

rede niht verstân).

Of course, one can understand the expression ‘rede’ that Eckhart is using

here as meaning ‘that which I am saying in this sermon’, that is, as just meaning: ‘my words’:

‘I beg you’ thus ‘to be so that you can understand my words’. But I do not see any reason

impeding from thinking that Eckhart is here rather describing the literary form he is using: this

text is therefore not a ‘sermon’ but, as I said, a ‘speech’ or ‘lecture’, that is, a ‘discourse’, or an

‘address’. The technical term in Latin is ‘collatio’, meaning a sort of ‘talk’ that was not

thought for a general public in the church or at the university, but to be delivered in private circles, in the case of this Speech on Poverty, or Rede von der armuot, surely to be delivered by

Eckhart only – precisely because of the radicalism of the used formulations – in presence of his

nearest disciples. We know some other Speeches, Discourses or Talks by Eckhart, namely his

so-called Erfordian Reden, or – even – Talks on Instruction. JOSEF QUINT edited them as

Eckhart’s Second Treatise, but instead they represent an anthology of ‘collationes’ that were –

most probably – delivered and discussed in Eckhart’s convent in Erfurt, as the title in some

extant manuscripts explicitly declares. This becomes particularly clear by comparing the

beginning of the Talks on Instruction with that of the Book of the divine Consolation, which

was undoubtedly published by Eckhart himself as a ‘Treatise’. The Talks on Instruction is

surely not a work by Eckhart himself but rather an anthology of Eckhart‘s texts – of Eckhart’s

collationes – published by some anonymous editor, most probably after Eckhart’s death. This is

the reason why we do not find any sentence taken from that work among the articles discussed

during Eckhart’s trial, neither in Cologne nor in Avignon. And this is also the explanation why

Eckhart’s Speech on Poverty did not play any role in his trial: since it is not a Sermon, it had

not yet been delivered by Eckhart at that time (ca. 1326–1329) in a public form or been published

in book form, but it was only known to his nearest circle of disciples, who are responsible for

the publication of this radical Speech, surely after the death of their master. Eckhart’s text on

poverty is – maybe – beautiful, yet not a beautiful sermon.

Wednesday, 16 November 2016

Jana Ilnicka presented a working paper on 'Relatio in Meister Eckhart's vernacular writing, as found in a re-discovered manuscript (Eisenach Ms. 1361)'

In this paper I am concerned with a Quaestio about 'relatio' in the newly found manuscript of Wartburg. This manuscript contains several texts (the extant is not established yet), which, according to their content, can be attributed to Eckhart alone, one of which is the present question about

relationship. It is here published for the first time and needs further exploration, for which this paper is the first attempt.

relationship. It is here published for the first time and needs further exploration, for which this paper is the first attempt.

87r-v

Meister Eghart und ouch ander meister sprechent /2 daz

zwei ding sind in gode: wesen und widersehen /3 daz da heisset relacio:

[Contra:]

nu sprechend die meister /4 daz des vader wesen /5 den

sun in der godheit niht gebird:

[Pro:]

Wan [da] der

vader nach sinem \/ [m.r.: wesen] sicht niht anders danne in sin bloßes wesen

/6 und schouwet sich selber da inne /7 nah aller siner kraft /8 und da

schouwet er sich blos an den sun /9 und an den heiligen geist: und sicht da

niht wan einkeit sines selben wesens

Wen aber der vader ein widerschouwen und ein widersehen

haben wil /10 sin selber in einer ander person /11 so ist des vader wesen in

dem widersehnenne geberend den sun

/12 und wand er im selber in dem widersehen so wol

gauellet /13 und im daz widerschouwen so lustelich ist /14 und wand er alle

wollust hat eweklich gehebt /15 darumbe so muost er /16 dis [wist] widersehen

|

<1> Meister Eckhart and other Meister too state, that there are two things in God: being and respect, that is called relatio.

[The counter-argument:]

Now the Meister say that the being of the Father does not give birth to the Son in the godhead.

[The argument:]

<2> If the Father sees according to his being he does not [see] anything except into his bare being and regards himself in there according to his entire power, and he only sees himself in the Son and in the Holy Spirit, hence he does not see anything but oneness of his very being.

If, however, the Father wants to have a regard and respect of himself in another person, it is the Father's being which gives birth to the Son in this respect.

<3> And because he is so delighted about himself in this respect, and the retrospection is so desirable for him and because he had such desire for eternity, therefore he must have this respect

|

<1> 'being and relation'

<2> respect is constitutive for persons in God

<3> eternity of relation

|

<87v> eweklichen hauen:

darumb so ist der sun ewig als der vader /2 und von dem

wolgeuallen und von der minne /3 so vader unde sun ze samen havend /4 so hat

der heilig geist sinen urspring:

und nun disv(?) minne zwichchen dem vader und dem sun ist

eweklich gewesen: darumbe so ist der heilig geist / als ewig als der vader

und der sun: und hand die dri person niht wan ein bloßes wesen und sind

allein underscheiden an den personen: wan des vaders person ward nie des suns

noch des heiligen geistes person: und alle drie \/ [m.r.: sind] ein ander

vremde an den personen / und sind doch ein in dem wesen

|

for eternity.

The Son is, therefore, as eternal as the Father, and he has the desire and the love jointly with the Father, from where the Holy Spirit has its origin.

Hence, the love between Father and Son has existed for ever.

Hence, the Holy Spirit is as eternal as Father and Son. And the three persons have only one simple being and are different only with regards to the persons. The person of the Father, namely, was never that of the Son nor the person of the Holy Spirit. And all three are alien to each other with regards the persons, although these are one in being.

|

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)